The Conflict That Changed Warfare Forever

The Hundred Years’ War, a series of conflicts spanning over a century (1337-1453) between the Houses of Plantagenet and Valois for control of the French throne, is often summarised by images of chivalric knights. Yet, beneath the armour and heraldry, this era was a crucible of radical military and siege technology. This period didn’t just feature battles; it pioneered entirely new ways of fighting that fundamentally shifted the balance of power from the noble knight to the common foot soldier. Understanding what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War is key to appreciating the transition from the medieval age to the early modern period.

The conflict’s origins are complex. Why did the Hundred Years’ War start? Primarily, it was a dynastic struggle following the end of the direct Capetian line in France, leading the English King Edward III to claim the French crown. This, combined with territorial disputes over Gascony and economic rivalries over the wool trade, provided the two major factors or causes of the conflict. The resulting war demanded innovation, and both the English and French armies were forced to adapt or face annihilation.

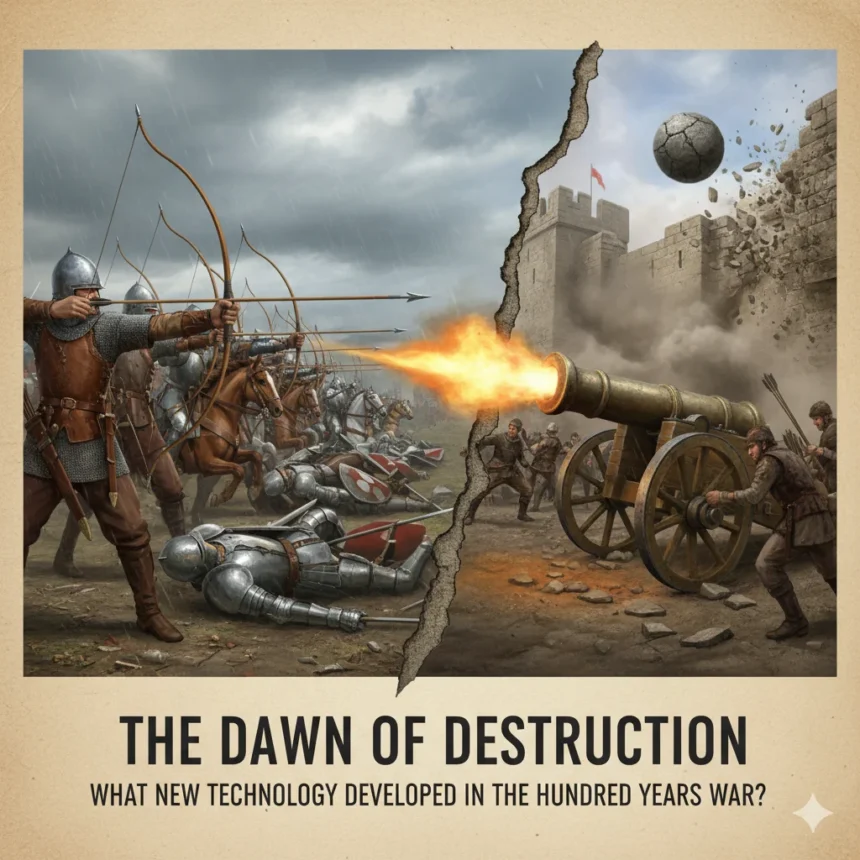

The Game Changers: Archery, Artillery, and Armour

The major technological developments can be grouped into three critical areas that forever changed the face of warfare: projectile weapons, siege engines, and personal protection.

The Reign of the Longbow: Precision and Power

The single most impactful technology to emerge was the widespread, dominant use of the English longbow. While not strictly new in terms of invention it had existed in various forms its strategic adoption, mass production, and training of dedicated, professional archers by the English military was revolutionary.

Technical Superiority of the Longbow

The typical English longbow was a powerful weapon, often six feet tall, capable of launching a yard-long arrow with incredible force.

- Rate of Fire: A well-trained longbowman could shoot between 10 to 12 arrows a minute, creating a deadly, high-volume arrow storm that shattered traditional knightly charges.

- Penetration: At close range, its arrows could pierce the mail and even plate armour of the time, as famously demonstrated at the Battles of Crécy (1346) and Agincourt (1415).

The longbow’s dominance fundamentally demonstrated what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War: the power of specialised infantry over aristocratic cavalry. It showed that disciplined commoners could defeat the elite knights, thus initiating a long, slow decline for the heavily armoured warrior class.

Gunpowder’s Debut: The Roar of Early Cannon

While gunpowder itself was a Chinese invention that slowly migrated westward, the Hundred Years’ War marked its decisive entry onto the European battlefield as a practical, war-winning technology. The question of what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War often leads directly to the earliest forms of artillery.

Early Artillery and the Siege

The initial gunpowder weapons, such as the ribaudequin (a type of organ gun) and early, crude cannon (like the French bombards), were notoriously temperamental, slow to load, and dangerous to their own crews. However, their psychological impact and raw destructive power against fortifications were unmatched.

- Siege Warfare: The true power of cannon lay in siege warfare. Prior to gunpowder, taking a well-fortified castle could take months or years. Cannons, despite their limitations, could breach medieval stone walls a feat previously requiring enormous time, manpower, and complex siege engines like trebuchets.

- The Rise of France: By the later stages of the war, the French forces, under leaders like Jean Bureau, perfected the organization and logistics of their artillery train. This allowed them to systematically dismantle English-held castles and strongholds, a major factor in determining who won the Hundred Years’ War (France, in 1453).

Responding to the Threat: Advancements in Personal Protection

The terrifying efficiency of the longbow and the growing menace of artillery spurred rapid innovation in defensive technologies. The knight, though threatened, did not vanish instantly; he simply became encased in better armour.

From Mail to Plate: The Evolution of Armour

The war accelerated the transition from flexible chain mail (or maille) to sophisticated full plate armour. Armourers quickly learned that the blunt force of a longbow arrow or the shock from early gunpowder projectiles could be better deflected by curved, solid plates of steel.

- Articulated Plate: The plate armour developed during this period was a masterpiece of engineering, featuring sliding rivets, jointed elbow and knee pieces, and specialised protection for joints, allowing for surprising mobility while providing near-complete coverage. This highly specialised equipment was another facet of what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War.

- Specialised Helmets: Helmets evolved from the simple great helm to more visually-appealing and functionally effective designs like the bascinet with a pivoting visor, offering better visibility and breathability while maintaining protection.

Beyond Land Battles: Naval Innovation and Fortification Changes

While land battles often dominate the narrative, the Hundred Years’ War also saw crucial developments in naval capabilities and the very architecture of defense.

The Shifting Tides: Naval Developments

Control of the English Channel was vital for the English to transport troops and supplies to France. This necessity spurred developments in shipbuilding and naval tactics.

The Emergence of the Carrack

The war saw the rise of the carrack, a revolutionary type of sailing ship that, while not invented during the war, became more common and evolved significantly. These large, three- or four-masted ships featured multiple decks, high castles at the bow and stern, and a greater carrying capacity than earlier cog-style vessels.

- Military and Trade Uses: Carracks were robust enough for both military transport and long-distance trade. Their size allowed for more soldiers, supplies, and eventually, larger cannons to be mounted on deck, fundamentally changing naval warfare from ramming and boarding to projectile exchanges.

- Logistical Backbone: The ability to move large numbers of troops, horses, and equipment across the Channel efficiently was a silent but crucial technological advancement. Without these logistical improvements, sustaining campaigns over such long distances would have been impossible. The evolution of shipbuilding is an often-overlooked aspect of what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War.

Fortifications in Flux: Adapting to Artillery

The arrival of gunpowder weapons forced a radical rethinking of defensive architecture. Medieval castles, designed to resist siege engines like trebuchets and determined infantry assaults, were vulnerable to cannon fire.

The Dawn of Star Forts (Proto-Bastions)

While true star forts (with their intricate, low-profile bastions) would develop later, the Hundred Years’ War saw the beginnings of adapting to the new artillery threat.

- Thicker Walls, Lower Profiles: New fortifications, or modifications to existing ones, began to feature much thicker, often earthen or rubble-filled walls, designed to absorb cannonball impacts rather than simply deflecting them. Walls also started to be built with lower profiles, presenting less of a target.

- Emphasis on Flanking Fire: Designers began to incorporate more sophisticated ways to provide flanking fire along walls, moving away from simple round towers to more angular projections that could cover dead zones and engage attackers from multiple angles. This foreshadowed the bastion system and demonstrated how quickly engineers responded to what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War. The very concept of defensible space underwent a profound re-evaluation.

The Legacy of Conflict: A New Military Landscape

The technological revolution of the Hundred Years’ War was part of a larger socio-economic shift. Why was the Hundred Years’ War important? Because it permanently altered the military and political landscape of Europe.

The Rise of Professional Armies

The specialised skill required to operate a longbow or manage a cannon meant that armies increasingly relied on trained, salaried professionals rather than feudal levies. This was the birth of the standing army. Furthermore, the immense cost of gunpowder, cannon, and mass-produced armor centralized military power in the hands of kings and powerful states, leading to the eventual effects of the Hundred Years’ War: the consolidation of royal power and the emergence of France and England as unified, distinct nation-states.

Beyond the Battlefield: Logistics and Administration

The scale and duration of the war also demanded innovations in logistics, finance, and administration. The English developed sophisticated methods for troop payment, provisioning, and transport across the Channel, laying the groundwork for modern military bureaucracy. Without these administrative innovations, sustaining a war for over a century would have been impossible, further cementing the significance of what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War not just in weapons, but in organization. The development of permanent taxation systems to fund these new armies and technologies also laid the groundwork for stronger central governments, giving the state Essential Skills for the Modern Technology Solutions Professional needed for long-term power.

The Cultural Shift: The Decline of Chivalry

The technological advancements, particularly the longbow and gunpowder weapons, also had profound cultural implications. The romanticized ideal of chivalry, with its emphasis on individual knightly prowess, began to wane. The new reality of warfare, where a commoner with a longbow could fell a heavily armored knight from a distance, or a cannonball could shatter a castle wall, emphasized massed firepower and strategic planning over individual heroics. This shift, while not a technology in itself, was a direct effect of the new technologies and represents a significant transition in medieval European society.

Conclusion

The Hundred Years’ War was more than a fight for a crown; it was a violent laboratory that birthed new ways of fighting and dying. The longbow and the cannon irrevocably changed the hierarchy of the battlefield, ushering in the age of the common soldier and the decline of the medieval knight. The military and administrative advancements forged in this long conflict, alongside the silent but crucial developments in naval capabilities and fortification design, are the true, enduring effects of the Hundred Years’ War, setting the stage for the Renaissance and the early modern world. The relentless drive to gain a military edge forced ingenuity, demonstrating how conflict, for all its devastation, can be a powerful catalyst for human innovation, answering comprehensively the question of what new technology developed in the Hundred Years War.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Who won the Hundred Years’ War?

France won the Hundred Years’ War. The conflict concluded in 1453 with the Battle of Castillon, after which the English retained only the port of Calais on the European mainland, ultimately solidifying French sovereignty and unity under the Valois dynasty.

2. What was the most significant technological development of the war?

While the longbow was militarily devastating, the most long-term significant technology was the widespread deployment of gunpowder and artillery (cannons). This technology marked a permanent shift in warfare, making medieval stone castles and city walls obsolete and centralizing military power with states that could afford to produce and maintain large siege guns.

3. Why was the longbow so revolutionary compared to the crossbow?

The longbow offered a significantly higher rate of fire (10-12 arrows per minute vs. 1-2 for a crossbow) and possessed excellent range and penetration power. While the crossbow was easier to train with, the longbow’s superior rapid-fire capability made it uniquely effective at disrupting massed charges of cavalry and infantry, as demonstrated at Crécy and Agincourt.

4. What were the two factors or causes of the Hundred Years’ War?

The two primary factors were:

- Dynastic Dispute: The claim by the English King Edward III to the French throne following the extinction of the direct line of the French Capetian dynasty.

- Territorial and Economic Conflicts: Disputes over the control of the wealthy French region of Gascony and economic rivalry over the wool trade and Flanders.

5. Besides weapons, what other kind of new technology developed in the Hundred Years War?

Beyond direct weaponry, the war led to significant advancements in naval technology (like the development of the carrack ship design), personal armor (the rapid evolution from mail to full, articulated plate armor), and crucially, military administration and logistics, as managing and funding a war that spanned over a century required new methods of taxation, provisioning, and organizing professional armies.